Basic Statistics - (04) R[2] Correlation & Regression

1. Scatterplots

-

plot()Saved in your console is a dataset called

womenwhich contains theheightandweightof 15 women (try typing it into your console and press enter to have a look). Let’s have a look at the relationship between height and weight through a scatterplot, using the R functionplot(). The first argument ofplot()is the x-axis coordinates, and the second argument is the y-axis coordinates.- Instructions

- In your script, make a scatterplot of

womenwithweighton the x-axis, andheighton the y-axis.- Use

main = *title here*insideplot()to add the title “Heights and Weights”

- Use

- In your script, make a scatterplot of

- Answer

# Plot height and weight of the "women" dataset. Make the title "Heights and Weights" str(women) plot(women$weight,women$height, main = "Heights and Weights")

- Instructions

2. Scatterplots

-

tableSaved in your console is a dataset called

smoking, which contains data about amount of tobacco smoked per day in a sample of 88 students. Thestudentvariable says whether a student is in high school, or university, and thetobaccovariable indicates how many grams of tobacco are smoked per day. We expected that there would be more tobacco use (the dependent variable) in university (the independent variable).We can make a contingency table of this data using the

table()function. While previously you may have used this with one variable, this time you will use it with two. The first variable used withtable()will appear in the rows, while the second variable will appear in the columns.-

Instruction

- Make a contingency table with amount of tobacco smoked as rows, and education as columns.

-

Answer

# Make a contingency table of tobacco consumption and education student tobacco table(student,tobacco)> # Make a contingency table of tobacco consumption and education > student [1] "university" "high school" "university" "high school" "university" [6] "high school" "high school" "university" "university" "university" [11] "high school" "university" "university" "high school" "high school" [16] "university" "high school" "university" "high school" "university" [21] "high school" "high school" "university" "high school" "high school" [26] "high school" "university" "university" "high school" "high school" [31] "high school" "high school" "university" "university" "university" [36] "university" "university" "university" "university" "high school" [41] "university" "high school" "university" "high school" "university" [46] "university" "high school" "high school" "high school" "university" [51] "high school" "university" "university" "university" "high school" [56] "university" "university" "high school" "university" "high school" [61] "high school" "high school" "high school" "high school" "high school" [66] "university" "university" "high school" "high school" "high school" [71] "high school" "university" "university" "university" "high school" [76] "high school" "high school" "university" "high school" "high school" [81] "university" "university" "university" "university" "high school" [86] "university" "high school" "university" > tobacco [1] "0-9g" "20-29g" "20-29g" "10-19g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "0-9g" "10-19g" [9] "20-29g" "20-29g" "0-9g" "20-29g" "0-9g" "20-29g" "0-9g" "10-19g" [17] "0-9g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "20-29g" "20-29g" "0-9g" "10-19g" "0-9g" [25] "10-19g" "10-19g" "20-29g" "0-9g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "10-19g" "20-29g" [33] "0-9g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "0-9g" "0-9g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "10-19g" [41] "20-29g" "0-9g" "0-9g" "10-19g" "20-29g" "10-19g" "20-29g" "0-9g" [49] "10-19g" "10-19g" "10-19g" "20-29g" "20-29g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "20-29g" [57] "10-19g" "10-19g" "10-19g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "20-29g" "10-19g" "20-29g" [65] "10-19g" "0-9g" "20-29g" "10-19g" "20-29g" "20-29g" "0-9g" "0-9g" [73] "0-9g" "10-19g" "10-19g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "10-19g" "0-9g" "0-9g" [81] "20-29g" "20-29g" "20-29g" "0-9g" "20-29g" "10-19g" "20-29g" "0-9g" > table(student,tobacco) tobacco student 0-9g 10-19g 20-29g high school 17 16 11 university 14 15 15

-

-

round(..., digit=)Have a look at the contingency table of tobacco consumption and education you made in the last exercise. It’s saved in your console as

st. Let’s use it to calculate some percentages!In this exercise you need to report your answers to one decimal place. You are free to do this manually, but if you want a quick way to do this through R you can use the

round()function. The first argument ofround()is the value that you want to round (this can be in the form of a raw number, or an equation), and the second argument isdigits =, where you specify the number of decimal places you want the number rounded to. For instance,round(12.6734, digits = 2)would return the value12.67.-

Instruction

- In your console, calculate the percentage of high school students who smoke 0-9g of tobacco per day.

- In your console, calculate what percentage of students who smoke the most are in university.

- Type your answers to one decimal place (without a percentage symbol) into your script

-

Answer

# What percentage of high school students smoke 0-9g of tobacco? mytable<-table(student, tobacco) smoke <- table(student,tobacco)[1] total<- sum(table(student,tobacco)[1,]) mytable smoke total round(smoke/total, digit=2) *(100) # Of the students who smoke the most, what percentage are in university? prop.table<-prop.table(mytable, 2) prop.table round(prop.table[2,2],digit=2)*100> # Of the students who smoke the most, what percentage are in university? > prop.table<-prop.table(mytable, 2) > prop.table tobacco student 0-9g 10-19g 20-29g high school 0.5483871 0.5161290 0.4230769 university 0.4516129 0.4838710 0.5769231 > round(prop.table[2,2],digit=2)*100 [1] 48

-

-

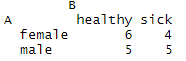

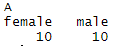

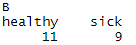

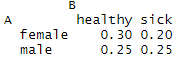

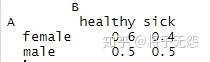

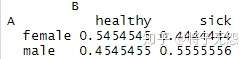

prop.tablemytable <- table(A,B) # 在这里,A变量的信息变成行,B变成列 mytable # 输出表格

margin.table(mytable, 1) # 对每一行的数据求和

margin.table(mytable, 2) # 对每一列的数据求和

prop.table(mytable) # 计算每一格数据占总数的比例

prop.table(mytable, 1) # 以行为单位,计算其中每个变量的占比,每行求和为1

prop.table(mytable, 2) # 以列为单位,计算其中每个变量的占比,每列求和为1

3. R 相关系数

-

cor()We can calculate the correlation in R using the function

cor(), which takes your two variables as it’s first argument. Try it out on the variables shown in the graph.-

Instruction

- In your script, calculate the correlation between

var1andvar2(these are saved in your console already)

- In your script, calculate the correlation between

-

Answer

# Calculate the correlation between var1 and var2 var1 var2 cor(var1,var2)> # Calculate the correlation between var1 and var2 > var1 [1] 20.47774 20.49618 19.14042 19.17094 19.67843 18.69623 18.57851 21.74491 [9] 19.71172 18.69113 19.93055 18.77507 20.80900 19.50785 20.45269 20.99963 [17] 20.46703 20.37605 21.70349 18.96454 21.32812 19.40571 21.61128 18.88733 [25] 18.53982 20.73216 18.38966 20.33207 20.76086 18.14633 > var2 [1] 8.711482 9.652311 9.478371 11.273473 11.824521 8.488692 10.110508 [8] 9.239204 9.330103 10.274520 8.976728 8.180602 9.332210 9.940702 [15] 10.880166 10.268513 9.980421 9.475053 8.590669 8.166011 9.841686 [22] 10.754427 9.087870 10.799931 11.490553 8.903598 9.465779 8.578797 [29] 8.757262 10.231936 > cor(var1,var2) [1] -0.2642027

-

4. Finding the line 回归系数

-

squared error

When we draw a line through our data, we measure error as the sum of the difference between the observation and the line. We usually square this so that positive and negative residuals don’t cancel each other out. The line that gives us the least error is our regression line.

To do this you should use the

sum()function, which returns the sum of all vectors provided between brackets. You can also put^2inside the brackets with your vectors in order to square the differences. For example,sum((vector1 - vector2) ^ 2).-

Instruction

y1contains the predicted values of y according to line 1,y2contains the predictes value of y according to line 2, andycontains the actual observed values of variable y.- In your script, calculate the squared error of line 1 and line 2.

-

Answer

# predicted values of y according to line 1 y1 <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) # predicted values of y according to line 2 y2 <- c(2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11) # actual values of y y <- c(3, 2, 1, 4, 5, 10, 8, 7, 6, 9) # calculate the squared error of line 1 sum((y-y1)^2) # calculate the squared error of line 2 sum((y-y2)^2)> # predicted values of y according to line 1 > y1 <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) > > # predicted values of y according to line 2 > y2 <- c(2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11) > > # actual values of y > y <- c(3, 2, 1, 4, 5, 10, 8, 7, 6, 9) > > # calculate the squared error of line 1 > sum((y-y1)^2) [1] 36 > > # calculate the squared error of line 2 > sum((y-y2)^2) [1] 46

-

5. The Regression Coefficients

-

a,b

We can find the regression coefficients for our data using the

lm()function, which takes our model as the first argument: first the y variable, followed by a~symbol, then the x variable. For instance: lm(y ~ x). The output labels the value of the intercept with ‘intercept’, and the value of the slope with the name of the independent variable. Let’s try this out with our study that investigated how money (independent variable) predicted prosocial behavior (dependent variable).-

Instruction

- In your script, write a line of code using the

lm()function to find the regression coefficients for how much money predicts prosocial behavior.

- In your script, write a line of code using the

-

Answer

# Our data money <- c(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10) prosocial <- c(3, 2, 1, 4, 5, 10, 8, 7, 6,9) # Find the regression coefficients plot(money, prosocial) plot(prosocial, money) lm(prosocial~money) lm(money~prosocial)

> # Our data > money <- c(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10) > prosocial <- c(3, 2, 1, 4, 5, 10, 8, 7, 6,9) > # Find the regression coefficients > plot(money, prosocial) > plot(prosocial, money) > lm(prosocial~money) Call: lm(formula = prosocial ~ money) Coefficients: (Intercept) money 1.2000 0.7818 > lm(money~prosocial) Call: lm(formula = money ~ prosocial) Coefficients: (Intercept) prosocial 1.2000 0.7818

-

-

lm()

In the last exercise you used

lm()to obtain the coefficients for your model’s regression equation, in the formatlm(y ~ x). takes the y variabWe can store this output and use it to add the regression line to your scatterplots! After you have created your scatterplot, you can add a line using the functionabline().abline()takes the intercept of the line as its first argument, and the slope of the line as its second argument. This makes it a pretty good candidate for storing yourlm()output as an object, and putting it straight intoabline. Let’s try this out!-

Instruction

- Use

lm()to obtain the regression coefficients for your model. Assign this to an object calledline - Use

abline()to add a line to your graph based on the output of “line”

- Use

-

Answer

# Your plot plot(money, prosocial, xlab = "Money", ylab = "Prosocial Behavior") # Store your regression coefficients in a variable called "line" line <-lm(money~prosocial) line # Use "line" to tell abline() to make a line on your graph abline(line[1],line[2], col = "red")> # Your plot > plot(money, prosocial, xlab = "Money", ylab = "Prosocial Behavior") > # Store your regression coefficients in a variable called "line" > line <-lm(money~prosocial) > line Call: lm(formula = money ~ prosocial) Coefficients: (Intercept) prosocial 1.2000 0.7818 > # Use "line" to tell abline() to make a line on your graph > abline(line[1],line[2], col = "red")

-

6. Examples

-

Regression

Let’s try to put it all together. You’ve conducted a study looking at how much money people have (dependent variable) and their education level (independent variable). Let’s check some different things in your data!

-

Instruction

- Calculate the Pearson r correlation coefficient between your two variables

- Calculate your regression coefficients and assign them to a new variable called

line - Print the regression coefficients you have assigned

- Make a scatterplot of your variables. Label the graph “My Scatterplot” (remember you can do this with the

main =argument) - Add the regression line to your scatterplot

-

Answer

# your data money <- c(4, 3, 2, 2, 8, 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 9, 8, 12) education <- c(3, 4, 6, 9, 3, 3, 1, 2, 1, 4, 5, 7, 10, 8, 7, 6, 9) # calculate the correlation between X and Y cor(money,education) # save regression coefficients as object "line" line<-lm(money~education) # print the regression coefficients line # plot Y and X plot(education,money, xlab = "education", ylab="money", main ="My Scatterplot") # add the regression line abline(line)

> # your data > money <- c(4, 3, 2, 2, 8, 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 9, 8, 12) > education <- c(3, 4, 6, 9, 3, 3, 1, 2, 1, 4, 5, 7, 10, 8, 7, 6, 9) > > # calculate the correlation between X and Y > cor(money,education) [1] 0.5846627 > > # save regression coefficients as object "line" > line<-lm(money~education) > > # print the regression coefficients > line Call: lm(formula = money ~ education) Coefficients: (Intercept) education 1.5744 0.6731 > > # plot Y and X > plot(education,money, xlab = "education", ylab="money", main ="My Scatterplot") > > # add the regression line > abline(line)

-

-

Contingency Tables

Let’s say you ran the same study looking at how much money people have and their education level, but you used categories instead. You measured education (the independent variable) as “high school” or “university” and money (the dependent variable) as “high” or “low”. This information is saved in your console as

td.-

Instruction

- Enter

tdinto your console and have a look at your contingency table - In your console, calculate what percentage of people with high money are university educated

- In your console, calculate what percentage of people with low money are high school educated

- What kind of education is linked to more money?

- Answer all questions in your script. Round numerical answers to one decimal place, and make sure text answers are in lower case and used as strings (i.e. using

"").

- Enter

-

Answer

td proptable<-prop.table(td,1) proptable # Percentage of people with high money that are university educated round(proptable[1,2],digit = 2) * 100 # Percentage of people with low money that are high schol educated round(proptable[2,1], digit = 2)*100 # What kind of education is linked to more money? "university"> td education money high school university high 1 5 low 8 3 > proptable<-prop.table(td,1) > proptable education money high school university high 0.1666667 0.8333333 low 0.7272727 0.2727273 > # Percentage of people with high money that are university educated > round(proptable[1,2],digit = 2) * 100 [1] 83 > > # Percentage of people with low money that are high schol educated > round(proptable[2,1], digit = 2)*100 [1] 73 > > # What kind of education is linked to more money? > "university" [1] "university"

-